ERO misses the mark

We assess the Good, the Bad, and the Noteworthy in ERO's report on relationships and sexuality education.

The Education Review Office (ERO) released its report into relationships and sexuality education (RSE) in New Zealand schools on 10 November. It is very much a mixed bag, containing some valuable insights but also several major flaws.

The Good

The report has given licence to the Minister of Education, Erica Stanford, to finally act upon the coalition government’s agreement to remove the current RSE Guide and it will be gone by the end of Term 1, 2025, replaced by an interim list of topics to be taught until a new curriculum has been written.

A group of writers “with expertise in RSE” will be convened by the Ministry of Education to write a new curriculum that “explicitly lays out what gets taught and when,” Stanford announced. This is good news if the writers are not in thrall to gender identity ideology and are wholly distinct from the ones who wrote the current ideological Guide that is soon to be ditched.

ERO recommends retaining the right of parents to withdraw their children from any parts of RSE lessons with which they disagree. This right has been removed from parents in Wales, so it is good news that ERO has not recommended following suit. (More about parents losing the right to consultation below.)

The prevalence of pornography and its pernicious effects have been highlighted. Two thirds of over 14 year olds have seen pornography and that increases to 75% by age 17, states the report. Addressing the harmful messages in pornography must be part of the new curriculum.

Older girls think boys should learn more about intimate relationships and consent, so they have realistic and healthy expectations of relationships. Girls told us that for boys to know what healthy relationships look like, they need to learn about social attitudes towards women, about sexual violence, and about the impacts of pornography. Secondary school girls told us that boys often don’t know that pornography isn’t real, which is concerning - we know that pornography rarely depicts meaningful consent, and often includes coercion and/or violence, particularly towards girls and women, as a ‘normal’ part of sexual encounters.

ERO has suggested extending compulsory RSE lessons into senior high school. (The subject is currently only compulsory up to the end of Year 10.) ERO found evidence that “boys’ needs are neglected due to an overemphasis on biology rather than relationships and this, coupled with peer and teacher expectations of masculine behaviour, doesn’t help boys to understand themselves, others, or cope with relationships.” As boys often mature later than girls, RSE in Year 11-13 may be more relevant for boys at that age, the report concludes.

The Bad

Gender identity treated as fact

As contemplated in our report when the review was first announced, most of RGE’s submission to ERO has indeed fallen on deaf ears. We provided ERO with international evidence of the destabilising effect of teaching “gender identity” as fact and how that concept disrupts the normal cognitive development of children and encourages body dissociation, but none of that information has made it into the report.

Instead of investigating the veracity of “gender identity” - the belief that we all have a gendered soul independent of our sexed bodies - ERO has unquestioningly accepted this minority belief and presents it in the report as an indisputable and universally accepted truth.

Social transition in schools ignored

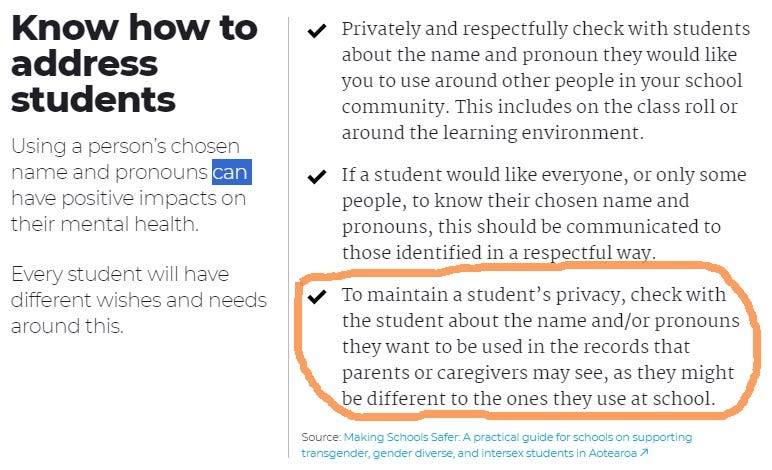

RGE’s submission also provided evidence that affirmation of an opposite sex (or no sex) “gender identity” in children is not a benign act and that social transition at school divides families and creates problems for the whole school community.

This aspect of school practice, that is probably the part of RSE that causes the most consternation and heartbreak for parents, and where schools have blatantly overridden parental rights to make decisions about their children, does not get a single mention in the ERO report.

“Gender identity” linked with sexual orientation

ERO repeatedly links “gender identity” with a new term that it does not define - “sexual identity”. We assume that what ERO means is “sexual orientation”, and that this is a sleight of hand to legitimise “gender identity” by associating it with the well-known category of same-sex attraction.

Sexual orientation is not an identity, it is a sexuality. “Gender identity” is not a sexuality, it is a belief system that teaches young gay and lesbian people that if they don’t fit sexist stereotypes, they are really the opposite sex and ought to modify their bodies to match the stereotypes.

Throughout its report, ERO repeats the phrase “gender identities and sexual identities” as if they are the same thing. By linking the two, ERO implies that claiming a “gender identity” is just the same as ‘coming out’ as same-sex attracted and that those who oppose “gender identity” are, by association, homophobic bigots.

Sex and gender conflated

The ERO Report does not contain a glossary so we are in the dark about how the Office defines sex and gender. It is the widespread misuse of these two words, informally as well as officially, that has created the confusion that has allowed the unscientific belief in “gender identity” to take hold in the community.

When ERO states that some parents of religious faith did not want gender identity taught because it doesn’t “align with some religions’ views on two genders (boys and girls only)”, it has used ‘gender’ as if it is a synonym for ‘sex’. The sentence should properly read that parents opposed the teaching of gender identity because of some religions’ views on two sexes (boys and girls only) - which, incidentally, is a scientific fact, not a “view”.

Asking the wrong question

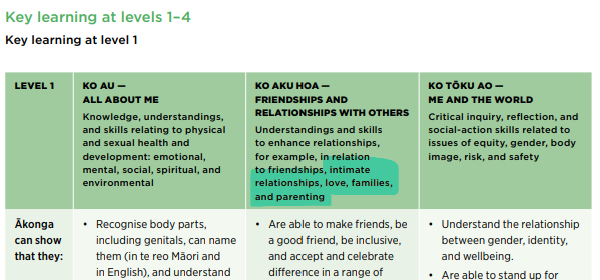

RGE believes there is a major flaw in ERO's report - the Office seems to have collected information only about the topics that are covered in schools, and not on how those topics are taught. Without the how, it is not possible for ERO to properly understand the concerns of parents. For example, nearly every parent is happy for their child to be taught about puberty, but when the child comes home having been taught that girls can have a penis and boys a vulva (as happens in the Navigating the Journey lessons), parents understandably feel betrayed.

ERO presented interviewees and survey respondents with a list of topics taught in RSE and asked them to rate whether they were covered “just right, too much, or too little”. The responses gathered are meaningless because they have not been matched to each school’s actual lesson content. One school’s teaching of “identity” or “acceptance and diversity” will not be the same as another’s, so a response of “just right” could mean anything from “the topic was touched on lightly” to “there was a week of intensive focus on it”.

ERO found that “many of the parents and whānau that we spoke to had limited knowledge of what was being taught for RSE due to lack of information.” In the puberty scenario above, a parent whose child does not divulge the content of the lesson will be none the wiser that they have been taught nonsense about swappable body parts and may well, in ignornace, have answered ERO’s survey with a “just right” tick for puberty.

Denial

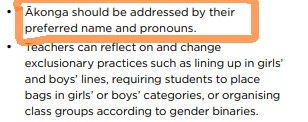

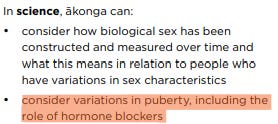

Claims by ERO that “gender identity” is “mostly taught in secondary schools” and that the RSE guidelines do not “include guidance to instruct students on how to change sex” are negated by the below images from the RSE Guide for Years 1 to 8.

The report implies opposition to RSE is coming exclusively from those with a conservative religious viewpoint, glossing over its own findings that 87% of parents want RSE to be taught in schools, but 34% of parents think that it “should be taught, but that it should be taught differently”. A third of NZ parents are religious conservatives? Really?

There is general agreement on teaching topics such as consent, relationships, contraception, managing emotions, and personal safety. The disagreement is over the teaching of “gender identity” where there is a split, with 37% of parents wanting it to be taught later and 25% wanting it taught earlier. 26% of parents want less taught about it and 22% want more taught.

Parents and whānau who report that too much about these topics are covered in RSE are worried that their children will be encouraged to ‘label’ themselves before they have matured, which could be confusing and limiting for them. Parents and whānau who have these concerns don’t necessarily want the topics to be excluded from RSE. Often, they want the coverage to be limited. They also place importance on ‘how’ the topics are covered, especially for younger students.

In the report’s own words, parents are seeking age-appropriate RSE with limits on when and how certain topics are covered. This underlines that the current RSE content is causing widespread disquiet for anyone who values scientific truth and the importance of allowing children to be themselves without adults introducing the fanciful idea that their body may be “the wrong one for them”.

The Noteworthy

Consultation or information?

ERO has suggested the government consider replacing the requirement on school boards to consult the community about RSE with a requirement to “inform parents and whānau about what they plan to teach and how they plan to teach it, before they teach it.” The rationale given is that, currently, consultation is either not happening at all, or it is not transparent, or it has been hard to manage and has caused division in the community and added stress for school staff.

ERO has highlighted a few instances where consultation meetings have become heated but failed to mention the many hundreds of parents who have taken their concerns to principals and school Boards in a measured and courteous way. RGE does not condone any abusive and threatening behaviour towards school staff but the public also ought to know that schools are not blameless in this debate. There are many schools where parents have been treated with disdain when they have asked for information about RSE. Some schools have said they cannot share lesson plans for copyright reasons. Some have required parents to go into the school to view physical copies of the resources. Some, despite parental objections, have insisted on teaching the scientifically false idea that humans can choose their sex. It is not surprising that emotions are running high.

There may be some merit in schools providing information rather than consultation, but that hinges entirely on whether or not the content of the new curriculum is controversial and also on whether schools can communicate with parents more effectively than they have in the past.

Poor communication

Some principals and Board chairs identified failings in school communications that RGE has also previously noted.

“Throughout the RSE guidelines there are several small, but what we perceive to be inflammatory, remarks that put people off the entire document, when a lot of it was really good content.”

“some language in RSE guidelines is not written in a way parents and whānau can easily understand and can lead to misinterpretation"

"in some cases, schools had shared the guidelines with parents and whānau, and the language really hadn’t been sensitised for this audience."

One standout example is the way the same headings are used in the RSE Guide for all year levels without an explanation that those topics will be covered over eight years of schooling. It is understandable that parents are up in arms when they see “intimate relationships” supposedly listed as a topic for five year olds!

Although ERO has placed the blame for the crisis we face in RSE on "misinformation”, and conservative parents who are “worried about changing attitudes”, it is clear that many schools have contributed to the problem by employing obtuse language and a high-handed attitude towards parents’ reasonable concerns.

As one of our supporters put it: “Parents want to know why their daughters want to wear breast binders and escape puberty when just 10 years ago that was not a thing. Parents suspect that school lessons asking 7 year old girls to contemplate if they could be in the wrong body if they enjoy climbing trees or doing maths, could, in some cases, have something to do with this. That’s why parents are worried.”

Differences for boys and girls

One of the most useful parts of the ERO report is the differences it has identified between boys and girls, both in the best timing for RSE and the relevance of the lesson content. The following quotations are excerpts from Chapter 4 of the report:

We know from the international literature that girls are more supportive of RSE being taught than boys, and especially about topics that impact them, such [as] gender stereotypes that can disadvantage them in society, as well as contraception and unplanned pregnancies.

The international literature also tells us that girls have a stronger interest than boys in the topic of managing feelings and emotions because they are generally more eager to discuss their thoughts, feelings, and worries.

We found that girls want to learn about other topics earlier. Girls are concerned about the possibility that by the time some topics are covered, particularly to do with bodies, consent, and romantic relationships, it is often ‘too late’.

We found that girls have strong views about what boys should cover in RSE. In particular, they wanted boys to cover topics that teach them how to interact with girls and women.

We know that boys reach maturity later than girls, which could explain why boys want to learn topics later. We heard that while boys in senior secondary school tend to have more buy-in to RSE learning, junior students show some resistance or ‘silly behaviours’ in RSE lessons. In the case of one boys’ secondary school, this led to a decision to delay teaching some RSE topics.

We heard that there could be a tendency for boys’ schools to prioritise ‘more academic’ learning and sports over ‘softer’ subjects like RSE. Boys in boys’ schools are left with gaps in their knowledge or have to teach themselves.

Eight in 10 students in girls’ schools learn about consent (81 percent) compared to less than six in 10 in co-ed schools (58 percent).

Both girls (75 percent) and boys (63 percent) want to learn about online safety earlier.

Girls are most (sic) at risk of online harm than boys. Girls are more likely to encounter unwanted digital communication through social media compared to boys, who are more likely to encounter unwanted digital communication through online gaming.

We heard that separating boys and girls for RSE was important to some parents and whānau.

These insights will be highly valuable for the writers of the new curriculum as well as useful guidance for teachers and parents in their conversations with adolescents.

What’s going on behind the scenes?

When the ERO review was first announced, we published a criticism of its design. Some of our doubts have now been allayed - for example, what appeared to be an insecure survey did have unique links attached that allowed ERO to filter out uninvited or multiple responses.

However, our criticism of the opaque nature of this consultation still stands. Minister Stanford did not publicly announce the ERO review at the start and has withheld the ministerial advice on RSE she received in January 2024. Now, Ms Stanford has announced that the curriculum is to be rewritten, and a list of topics to be covered will be available from Term 1 2025. This very short timeframe suggests that planning is already well underway for the curriculum changes and there may be very little opportunity for community input.

RGE has written to Minister Stanford to ask who will be on the curriculum writing team and to emphasise that gender identity ideology must not appear in the new curriculum, except when it is approached from a critical thinking perspective. (See our suggested lesson plans on this and other RSE topics.)

All children deserve to be taught, at the appropriate age, scientific facts about how their bodies work and how to develop positive relationships, not to be exposed at school to ideological beliefs steeped in stereotypes.

In a TV One report, Minister Stanford commented that, if the new curriculum was prescriptive enough, there would be no need for new guidelines. We beg to differ. Although the current RSE Guide will be gone, there are many other resources published by the Ministry of Education that advise schools to carry out damaging practices like secret transitioning.

New guidance to schools must accompany the new curriculum. In our letter we have (again) urged Minister Stanford to follow the advice of the Cass Review and immediately instruct schools to take no further part in introducing or promoting the social transition of their students.

In our previous substack, Trust depends on Truth, you can read more about the negative impacts on all relationships when adults do not tell children the truth.

This might seem a minor point, but I "smell a rat" in the subtle Māorification of the RSE, referring to students / pupils as "ākonga" and frequently intermingling Māori words throughout the English text. There appears to also be a requirement that all students are to know all the names of body parts in both English AND Māori.

Don't get me wrong - I'm not into bashing the Māori language in any shape or form - but there is a strong odour of "woke" in the way the curriculum includes token Māori terminology, seemingly to make it attractive to those riding on the "inclusivity" and "toitu te tiriti" bandwagons. It totally smacks of virtue-signalling!

Great, very informative article RGE. Thank you for all your work.